Heroin

In 1898, the German pharmaceutical company Bayer began marketing heroin—whose name comes from the German word heroisch, meaning "powerful."

The product was marketed as a cough remedy made from a supposedly non-addictive morphine derivative. It was also used as a cure for morphine addiction—which unfortunately caused large numbers of users to become heroin addicts.

In part because of the growing population of "junkies" (a term that may derive from the fact that some supported their addictions by selling scrap metal), Bayer eventually ceased production and lost its trademark.

In 1914, American officials began regulating opiates, including the generic, powdered version of heroin.

Granola

Granola was not, in fact, invented by hippies in the 1960s—but they did popularize the name.

The story of this cereal begins a century earlier, with health food advocates of the 1860s.

At his health sanitarium in upstate New York, Dr. James C. Jackson created "granula" for his patients. Jackson formed his "granula" by breaking up sheets of twice-baked whole grain flour (then called graham flour after its developer, Sylvester Graham).

A decade later, Dr. Jackson sued Dr. John Harvey Kellogg of the Battle Creek Sanitarium for calling his own similar invention "granula." Kellogg renamed his version granola, but never really marketed it.

Back-to-basics food lovers revived Kellogg's coinage in the 1960s; the generic usage of the word granola appeared in print in 1970.

Jungle Gym

In 1920, Chicago lawyer Sebastian Hinton trademarked the Junglegym (one word).

He modeled his structure after one devised by his mathematician father, who had envisioned children learning about three-dimensional space by climbing to specific x, y, and z coordinates.

Over the decades, the beloved structure has been updated, and the trademark status lost. However, newer designs still honor what the inventor called the "monkey instinct" of kids.

The (two word) term jungle gym first appeared in 1923; the never-trademarked, closely related term monkey bars traces to 1955.

Pablum

The term pablum means "something insipid, simplistic, or bland"—which is unfortunate, because its namesake was a brilliant invention.

In 1930, a trio of Canadian pediatricians created a cereal called Pablum (a name based on the Latin word pabulum, meaning "food" or "fodder") to help prevent rickets in infants. Packed with vitamins and minerals, their cereal was precooked to be easily digestible by young bodies. The product was a lifesaver and a hit.

Because of the cereal's lack of flavor, however, the word pablum developed its metaphoric meaning—a sense that dates at least as far back as 1948.

Pogo Stick

In 1919, after a shipment of wooden jumping sticks rotted en route from Germany to the US, George Hansburg patented and trademarked a metal version: the Pogo.

He introduced it to the chorus girls of the Ziegfeld Follies, who used the stick on stage. The ensuing Pogo fad of the 1920s even included a couple getting married on them.

But by 1921, pogo stick was being used generically, and pogo is no longer protected by trademark.

Band-aid

In the early 1920s, a woman named Josephine Dickson—who tended to injure herself in the kitchen—grew tired of trying to wrap her cuts with bulky, clumsy gauze.

This inspired her husband, Earle, to invent what became a simpler, sleeker alternative: sterilized, pre-made adhesive bandages. Earle offered them to his employer, Johnson & Johnson—whose marketing triumphs included shipping free Band-aids to the Boy Scouts.

Although the noun Band-aid is still protected under trademark (i.e., "Band-aid brand"), the adjective band-aid is generic. Since 1970, folks have been using such the term in such phrases as "a band-aid solution."

Ping-Pong

In the late 1800s, some creative Brits reportedly used cigar box lids to bat rounded wine corks across a table. A line of standing books provided the net.

The game quickly gained a number of names, among them table tennis, gossima, flim-flam, and also—based on the sounds of the sport—ping-pong.

Before long, the British manufacturer J. Jaques & Sons had registered the term Ping-Pong. The American rights to that name were soon purchased by Parker Brothers (and are now owned by Escalade Sports).

By 1934, ping-pong had acquired a generic meaning: "something resembling a game of table tennis, especially a series of usually verbal exchanges between two parties."

That's fitting, because by then Parker Brothers and the International Table Tennis Federation had spent years going back and forth over the names.

Since 1988, table tennis (not Ping-Pong) has been an Olympic sport.

Moxie

These days, moxie is a synonym for energy and pep, courage and determination, know-how and expertise.

The original moxie was a patent medicine and tonic—Moxie Nerve Food—invented by Dr. Augustin Thompson and sold in New England in the 1870s. According to one story, Dr. Thompson got the name from a Lieutenant Moxie who discovered the South American plant that was the elixir's secret ingredient. Another story traces moxie to an Algonquin word.

Within a decade, Thompson had carbonated Moxie and was marketing it as a beverage with a "delicious blend of the bitter and the sweet." The soft drink and its advertising slogans (among them Make Mine Moxie!) caught on around the country.

By 1930, moxie had acquired its earliest modern sense of "energy, pep." Appropriately enough, although the drink's popularity has fizzled in most of the U.S., the word moxie determinedly lives on.

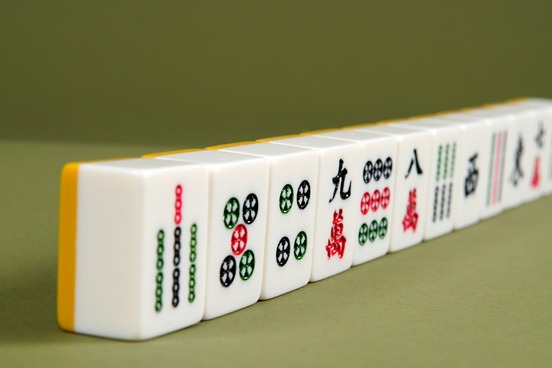

Mah-Jongg

Mah-jongg (spelled with one or two gs) is a game of Chinese origin in which players try to create winning hands from a set of domino-like tiles.

The game was imported to the U.S. after World War I by Joseph P. Babcock, who also coined (and trademarked) the name. The game's Chinese name, which sounds similar to "mah-jongg," means "sparrow." A sparrow or a mythical "bird of 100 intelligences" appears on one of the tiles.

Mah-jongg became a fad in the 1920s, but Babcock was more interested in promoting the game than in protecting his trademark, and mah-jongg became a generic term.

In the U.S., the game enjoys periodic revivals, but has never regained its early popularity. In China, it's still widely played.

Thermos

What we now know as the thermos was invented in 1892 by British scientist Sir James Dewar, a scientist at Oxford University.

A German company marketed Dewar's invention, and soon thermos became the generic term for any container with a vacuum between an inner and outer wall that helps its contents retain their initial temperature (rather than cool or warm to the ambient temperature).

The American Thermos Bottle Company bought the trademark rights in the U.S., but never managed to stuff the language back into its bottle. After decades attempting to prohibit the generic use of thermos, the then-renamed American Thermos Products Company lost its trademark in court in 1962.

So where did the word come from? A contest: the winning submission recalled the Greek thermē, meaning "heat."