May-December romance

A May-December romance is one that occurs between two people significantly far apart in age. How wide that gap is can vary, depending on one's point of view.

This sexy movie centers around a May-December romance between Stella, an overachieving 40-something divorcée and a handsome 20-something whom she meets while vacationing in Jamaica.

— Karla Pope, Good Housekeeping, 2 Feb. 2021

Why those two months? Think of the calendar as a metaphorical timeline of a life. January is when things begin anew (represented by a New Year's baby). May is spring, representing youth, when everything is newly flowering and fresh. December, at the end of the year, symbolizes the winter of older age, though as our example shows, the older person in the couple might still have a lot of years ahead of them.

Monday-morning quarterback

It's easy to second-guess, especially when you're a football fan. Monday-morning quarterback plays on a notion familiar to any fan who has questioned their favorite team's offensive strategies. Since most college and pro games are played on weekends, football fans often have a lot of talk about when they're back at work on Monday.

The idea is so familiar that we now find Monday-morning quarterback used metaphorically in contexts outside of the game:

As residents in Tucson watched it burn across the mountain range, some wondered if the fire really needed to get so big, or if the firefighting strategy failed at the beginning by not quickly smothering the fire while it was small.

“It’s easy to be a Monday-morning quarterback,” said Donald Falk, a fire ecologist and professor at the University of Arizona. “They were doing all they could.”

— Alex Devoid, The Arizona Daily Star, 27 June 2020

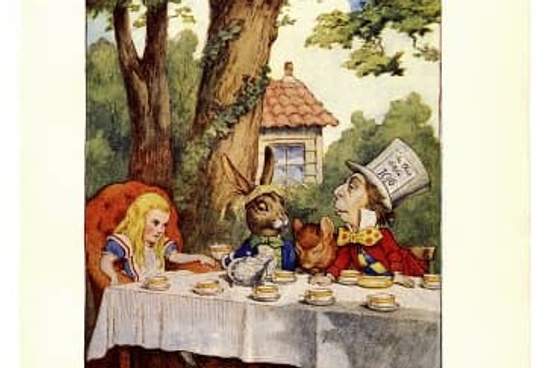

Mad as a March hare

You're more than likely familiar with March Hare from the name of the character that appears at the tea party in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

'I've seen hatters before,' she said to herself; `the March Hare will be much the most interesting, and perhaps as this is May it won't be raving mad--at least not so mad as it was in March.'

— Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1865

There is no specific creature called the March hare; the term is applied to the European hare (Lepus europaeus, also called the brown hare), with allusion to its aggressive breeding habits at the end of winter. Early forms of the phrase mad as a March hare date to the 16th century, long before Alice's tea party.

'Well! Look after him for the present, and--let me see--three days from this time let the other woman come here, and we'll see if we can make a bargain of it. About nine or ten o'clock at night, say. Keep your eye upon him in the meanwhile, and don't talk about it. He's as mad as a March hare!'

'Madder!' cried Mrs Gamp. 'A deal madder!'

— Charles Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit, 1844

October surprise

Sometimes, when it comes to elections in the United States, it feels as though the next one begins almost as soon as the last one ends. But in reality, many voters don't start paying attention to an election until the final days leading up to the vote. October surprise refers to an event occurring during the last weeks of an election (held in November) that has the power to sway undecided voters.

Four months later—11 days before the 2016 presidential election—Comey sent a letter to Congress saying he was reopening the investigation in light of new information found, but not yet examined, by the F.B.I. It was now the Democrats’ turn to erupt in rage—a rage that only grew when two days before the election Comey announced there was nothing new or incriminating about the purportedly new information. The “October surprise” dominated the news cycle in the crucial last days of the election, allowing Donald Trump to claim on the campaign trail that Hillary would soon be indicted, and to lead his followers in chanting, “Lock her up!”

— Bethany McLean, Vanity Fair, 21 Feb. 2017

The earliest use of October surprise can be traced to 1980, when the presidential election between Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan played out against the backdrop of the Iran hostage crisis. Members of Reagan's campaign used the phrase in anticipation that the release of the hostages before the election would be a convenient boon to Carter, the incumbent. That "October surprise" never happened—the hostages weren't released until after the election, won handily by Reagan—but the term stuck.

A month of Sundays

A month of Sundays is an expression used to mean "an extremely long time," often expressed in negative constructions:

The house servants had never gone into the bottle when they had headaches for they all believed that what worked for Maude would never in a month of Sundays work for a slave.

— Edward P. Jones, The Known World, 2003

The phrase dates to the mid-18th century and perhaps alludes to the idea that Sundays, set aside for church or rest, might proceed at a slower pace than a busy workday. John Updike used the phrase somewhat punningly as the title of his novel about an adulterous clergyman sent away for 30 days' worth of confinement.

The phrase a week of Sundays, less frequently encountered, has the same meaning.

Freaky Friday & Groundhog Day

Freaky Friday might not be a common expression, but the idea is easily understood by anyone familiar with the 1972 novel by Mary Rodgers, later made into a film starring Barbara Harris and Jodie Foster (1976) and, later, Jamie Lee Curtis and Lindsay Lohan (2003).

In that story, a mother and her teenage daughter switch places by inhabiting each other's bodies for a day. The book and films have enough of a presence in popular culture for Freaky Friday to turn up as a phrase meaning "to switch places":

When they first got to be friends, years ago, "we Freaky Fridayed," [singer Jenny] Lewis said. [Singer Annie] Clark, eager to get away from New York, moved to Los Angeles, and Lewis, escaping some personal rubble in California, moved into Clark's East Village apartment.

— Nick Paumgarten, The New Yorker, 28 Aug. 2017

Another movie title seeing similar growth is Groundhog Day, for a day or routine that seems to repeat itself endlessly, referring to the 1993 Bill Murray comedy in which a crotchety weatherman finds himself living the same day over and over.

But the kitchen timer feature makes this one actually useful—and while many of us are stuck in a groundhog day of cooking endless family meals at the moment, it could provide some much-needed entertainment.

— Alexandra Jardine, AdAge, 14 Jan. 2021