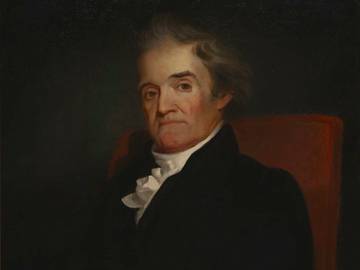

April 14 is the anniversary of the publication of Noah Webster’s famous dictionary, which bore the deliberately patriotic title An American Dictionary of the English Language. Here is the rationale for his project from the Preface:

It is not only important, but, in a degree necessary, that the people of this country, should have an American Dictionary of the English language; for, although the body of the language is the same as in England, and it is desirable to perpetuate that sameness, yet some differences must exist. Language is an expression of ideas; and if the people of one country cannot preserve an identity of ideas, they cannot retain an identity of language.

Noah Webster's famous dictionary, published on this day in 1828, shaped what we now consider American spelling. But ultimately, the choice of which spellings to adopt is made in the most democratic way possible: by public use and acceptance.

In 1828, the United States was still a new and fragile country—far from a world power. With that in mind, it’s remarkable to note that Webster went on to make an extraordinary prediction:

It has been my aim in this work, now offered to my fellow citizens, to ascertain the true principles of the language, in its orthography and structure; to purify it from some palpable errors, and reduce the number of its anomalies, thus giving it more regularity and consistency of forms, both of words and sentences; and in this manner, to furnish a standard of our vernacular tongue, which we shall not be ashamed to bequeath to three hundred millions of people, who are destined to occupy, and I hope, to adorn the vast territory within our jurisdiction.

Considering that the census of 1830 listed the population of the U.S. as 13 million people, Webster showed astonishing clairvoyance with this statement. In the preface of his smaller dictionary of 1806, he asserted that American English would be “spoken by more people, than all the other dialects of the language,” which also came true. He also gave a perfect linguistic rationale for a new dictionary:

Every man of common reading knows that a living language must necessarily suffer gradual changes in its current words, in the significations of many words, and in pronunciation.

It’s interesting to see that his stated goal with the dictionary was to “purify” the language, not by inventing new rules but, according to Webster, by reasserting old ones. His ideas about spelling contributed to what we now recognize as the differences between American English spellings and British English spellings—think of colour/color, or theatre/theater, or realise/realize.

We usually understand Webster’s spelling reforms as a purifying zeal for simplicity and American identity, but the truth is a bit more complex. He recommended deleting the a in words like leather and feather, asserting, correctly, that the a served no phonetic purpose and that it was not present in Old English. (Covering his bets, he put both spellings side-by-side in his 1828 edition; in the 1806 he set the letter a in those words in italics.) He invoked rules of Latin phonetics to remove the k from words like publick and musick: “To add k after c in such words is beyond measure absurd.”

Webster also preferred tung for tongue, not only because it was more phonetically spelled, but because it was an Old English spelling. As we know, tung didn’t catch on, nor did lether and fether. Despite his desire to control and fix the language, the ultimate decision of which spellings are adopted is made in the most democratic way possible: by public use and acceptance. Webster's struggle to embrace inevitable change in some cases and to retain recognizable convention in others mirrors the way that languages evolve: slowly and untidily.