Accord

Accord appears in Old English with the meaning "to reconcile" or "to bring into agreement," which was borrowed from its Anglo-French etymon, acorder, a word related to Latin concordāre, meaning "to agree." This original sense of accord is transitive, and in modern English it still occurs but infrequently. Its transitive sense "to grant or give as appropriate, due, or earned"—as in "The teacher's students accord her respect"—is more often encountered.

So your hope for any new president—small tests come that are successfully met. And then they feel good inside, they get larger and then they move on to the larger crises. But crises don't accord themselves to presidential needs.

— Doris Kearns Goodwin, quoted on NBC, 24 Dec. 2000In according themselves with Title IX, schools are often faced with two choices: adding women's opportunities or cutting men's. As most schools are finding out, abiding by Title IX often means both.

— Daniel Roberts, The Montana Kaimin (University of Montana), 22 Oct. 1997

On the flip side, the verb's intransitive sense "to be consistent or in harmony" (which is usually used with with) is frequently found, as in "The testimony did not accord with the known facts" or "His plans for the company did not accord with other investors."

The noun accord has the meaning "agreement" or "conformity." It often occurs in legal, business, or political contexts where it is synonymous with treaty and other similar words for formal agreement.

Agreement

In Middle English, agree was formed agreen and had the various meanings of "to please, gratify, consent, concur." It was borrowed from Anglo-French agreer. That word is composed of a-, a verb-forming prefix going back to Latin ad-, and -greer, a verbal derivative of gré, meaning "gratitude, satisfaction, liking, pleasure, assent." The French base derives from Latin grātum, the neuter of grātus, meaning "thankful, received with gratitude, welcome, pleasant." Semantically, the etymology of agree is very agreeable.

In Anglo-French, agrément referred to an arrangement agreed to between two or more parties as well as to the action or fact of agreeing, consenting, or concurring (more on those "c" words later). Late Middle English adopted the word as agrement with the same meanings, which are widely used today. The modern spelling, agreement, was used contemporaneously with agrement.

In grammar, agreement refers to the fact or state of elements in a sentence or clause being alike—that is, agreeing—in gender, number, or person. For example, in "We are late" the subject and verb agree in number and person (there's no agreement in "We is late"); in "Students are responsible for handing in their homework" the antecedent ("students") of the pronoun ("their") agree. The antecedent of a pronoun is the noun or other pronoun to which the pronoun refers. A synonym of this agreement is concord.

What meane you by Concords? A. The agreements of words togither, in some speciall Accidents or qualities: as in one Number, Person, Case, or Gender.

— John Brinsley, The Posing of the Parts, 1612

Assent

Assent descends from Latin assentire, a combination of the prefix ad- (meaning "to" or "toward") and sentire ("to feel" or "to think"). The meanings of the Latin roots imply having a feeling or thought toward something, and that suggestion carries over to English's assent, which denotes freely agreeing with or approving something that has been proposed or presented after thoughtful consideration. Assent is used as a noun or a verb with the meaning "to agree or approve."

The patient gave her assent to be part of the medical study.

Many at the meeting nodded in assent.

Both parties assented to the terms of the contract.

Bargain

Bargain, as a noun and verb, began being exchanged in English during the 14th century. We know that it developed from Anglo-French bargaigner, meaning "to haggle," but its history thereafter is unclear. The first known use is as a noun referring to a discussion between two parties on the terms of agreement.

I do not care, I'll give thrice so much land / To any well deserving friend; / But in the way of bargain, mark ye me, I'll cavil on the ninth part of a hair.

— William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part I, 1598

That sense fell into obsolescence by the end of the 17th century; however, another sense of bargain from the 14th century, referring to an agreement (concluded through discussion) that settles what each party gives or receives to or from the other, survives. It wasn't until the 16th century that bargain began being used as a word for what is acquired through such an agreement by negotiating, haggling, dickering … by bargaining.

From those visits to unsanitary Houndsley streets in search of Diamond, he had brought back not only a bad bargain in horse-flesh, but the further misfortune of some ailment which for a day or two had deemed mere depression and headache, but which got so much worse….

— George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1871

This nominal sense is often used without a qualifying adjective (such as good or bad) to indicate something that is bought or sold at a price which is lower than the actual value—in other words, a good deal: "At that price, the house is a bargain" or "We got a bargain on tickets for our flight."

Bond

Early recorded evidence of bond goes back to the 12th century and ties the word to things that bind, constrict, or confine (such as a fetter). The word is believed to be a phonetic variant of band, which had the same meaning.

From the early 14th century, bond has been used for various kinds of "binding" agreements or covenants, such as "the bonds of holy matrimony." Later, this sense was generalized to any "binding" element or force, as "the bonds of friendship." In 16th-century law, it became the name for a deed or other legal instrument "binding" a person to pay a sum of money owed or promised.

Go with me to a notary, seal me there / Your single bond, and, in a merry sport, if you repay me not on such a day, / In such a place, such sum or sums as are / Express'd in the condition, let the forfeit / Be nominated for an equal pound / Of your fair flesh....

— William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, 1596-97

In U.S. law, bond specifically refers to a formal written agreement by which a person undertakes to perform a certain act (e.g., appearing in court or fulfilling the obligations of a contract). The failure to perform the act obligates the person to pay a sum of money or to forfeit money on deposit. A surety usually is involved, and the bond makes the surety responsible for the consequences of the obligated person's behavior. Bonds are often given to people suspected of committing a crime ("The accused was released on $10,000 bond"), but any person obligated to preform a duty might have to give bond.

Cartel

Cartel is ultimately derived from the Greek word for a leaf of papyrus, chartēs, and is thus a relative of card, chart, and charter. In Latin, the Greek word became charta and referred to either the leaf or to that which is written on papyrus (such as a letter or poem). Old Italian took the word as carta and used it to denote a leaf of paper or a card. The diminutive form cartello served to denote a placard or a poster and then acquired the sense of "a written challenge or letter of defiance." The French borrowed cartello as cartel with the meaning "a letter of defiance," and English then borrowed the French word in form and meaning.

Indignant as he was at this impertinence, there was something so exquisitely absurd in such a cartel of defiance, that Nicholas was obliged to bite his lip and read the note over two or three times before he could muster sufficient gravity and sternness to address the hostile messenger, who had not taken his eyes from the ceiling, nor altered the expression of his face in the slightest degree.

— Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby, 1838

During the 17th century, cartel came to refer to a written agreement between warring nations especially for the treatment and exchange of prisoners. This usage is exemplified by Bishop Gilbert Burnet in his History of His Own Time (1734): "By a cartel that had been settled between the two armies, all prisoners were to be redeemed at a set price, and within a limited time."

German borrowed the French word cartel as Kartell. During the 1880s, the Germans found a new use for the word to denote the economic coalition of private industries to regulate the quality and quantity of goods to be produced, the prices to be paid, the conditions of delivery to be required, and the markets to be supplied.

English took up this German usage around 1900 but applied it mainly to international coalitions of private, independent commercial or industrial enterprises designed to limit competition or fix prices. American antitrust laws ban such cartels or trusts as being in restraint of trade, but they exist internationally with perhaps the most familiar one being the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).

Compact

Since the 1500s, compact has been used in English to designate an agreement or covenant between two or more parties. It descends from Latin compactum ("agreement"), a noun use of compactus, the past participle of compacisci ("to make an agreement"), which joins the prefix com- ("with, together") with pacisci ("to agree or contract"). Pascisci is also the source of pact, an earlier synonym of compact.

The Mayflower Compact of 1620 was drafted to bind the passengers landing at Plymouth into a political body and pledge members to abide by any laws that would be established.

Again, witchcraft, a devilish art, whereby some men and women, having made a compact with the devil, either expressly or implicitly, are enabled, with God's permission, and by the assistance of Satan, to produce effects beyond the ordinary course and order of nature, and these for the most part rather mischievous to others, than beneficial to themselves."

— William Burkitt, Expository Notes, with Practical Observations on the New Testament, 1789

Latin compactus is also the source of the adjective compact, which is used to describe things smaller than others, using little space, or having parts that are close together. This compactus, however, is the past participle of Latin compingere, meaning "to put together." The verb is a compound of com- and pangere ("to fasten"). The adjective is unpacked in 14th-century English, and by the 17th century, the related noun referring to things compact (modern applications are for cosmetic cases or automobiles) settles in.

Composition

Composition derives from Latin composito, which itself is from compositus, the past participle of componere, meaning "to put together." Since its entry in the 14th century, composition has gained a number of senses based on arranging or putting something together. One group of senses refers to the results of composition or, rather, composing.

Students know composition as the name for a brief essay (the putting together of words and sentences); philharmonic aficionados know it as the name for a long, complex piece of music (the arrangement of musical sounds); historians and lawyers know it as a term for a mutual settlement or agreement, such as a treaty or compromise (the coming together and reconciling of differences).

Obviously all of us know that the composition that was reached in Korea is not satisfactory to America, but it is far better than to continue the bloody, dreary sacrifice of lives with no possible strictly military victory in sight.

— Dwight D. Eisenhower, address, 19 Aug. 1954

Compromise

15th-century English borrowed Anglo-French compromisse, meaning "mutual promise to abide by an arbiter's decision," virtually unchanged in form and definition. The familiar usage of compromise for the settlement of differences by agreeing to mutual concessions soon followed.

Shall we, upon the footing of our land, / Send fair-play orders and make compromise, / Insinuation, parley and base truce / To arms invasive?

— William Shakespeare, King John, 1623All government, indeed every human benefit and enjoyment, every virtue, and prudent act, is founded on compromises and barter.

— Edmund Burke, speech, 22 Mar. 1775

The French word is derived from Latin compromissum, which itself is related to the past participle of compromittere (promittere means "to promise"). In English, compromit was once used as a synonym of the verb compromise in its obsolete sense "to bind by mutual agreement" and in its modern sense "to cause the impairment of."

Hence it is argued that the ratification of the late treaty could not have compromitted our peace.

— Henry Clay, letter, 27 July 1844

As a verb, compromise indicates the giving up of something that you want in order to come to a mutual agreement ("The union and employer agreed to compromise"). Another sense is "to expose to suspicion, discredit, or mischief," as in "The actor's career has been compromised by his politically incorrect tweets" or "The editor-in-chief would not compromise his principles." And as mentioned above, it can imply exposing someone or something to risk, endangerment, or serious consequences. Confidential information, national security, or one's immune system might be said to be "compromised."

Concord

Concord is from Latin concord-, concors, both of which denote "agreeing" and are rooted in com-, meaning "together," and cord-, cor-, meaning "heart." Literally, the Latin terms united translate as "hearts together," which gives reason as to why the earliest meanings of English concord include "a state of agreement," "harmony," and "accord." The word's sense of "agreement by stipulation, compact, or covenant" beats next, and in time, concord designates a treaty establishing peace and amicable relationships between peoples or nations. Thus, two countries may sign a concord on matters that have led to hostility in the past and live in peace and concord.

He now openly proclaimed that he had no intentions of abiding by the concord of Salamanca, and that he would never consent to an arrangement prejudicing in any degree his, and his wife's, exclusive possession of the crown of Castile.

— William H. Prescott, The History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, 1838

If you recall, concord is also synonymous with grammatical agreement.

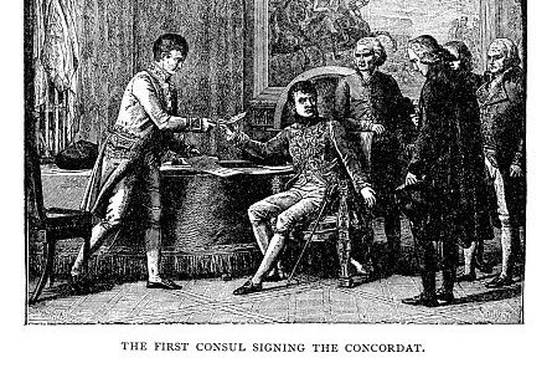

Concordat

Concordat is a French word for a formal agreement between two or more parties. It is synonymous with words like compact and covenant, but during the 17th century it was appointed as the official name for an agreement between church and state for the regulation of ecclesiastical matters. A historic concordat is one concluded in 1801 between Napoleon Bonaparte as the first consul and Pope Pius VII. It defined the status of the Roman Catholic Church in France and regulated the relations between church and state.

Concurrence

Like concur ("I concur with the assessment"), concurrence implies agreement. The verb originates from Latin concurrere, meaning "to assemble in haste, collide, exist simultaneously, be in agreement," and the noun—concurrence—derives from Latin concurrentia, "coming together, simultaneous occurrence." Usage of concurrence concurs with its Latin ancestor's. Additionally, concurrence has the extended meaning "agreement in action or opinion."

The month of December, with the concurrence of Hanukka and Christmas, has become a period devoted by many to interfaith understanding.

— Haim Shapiro, The Jerusalem Post, 10 Jan. 1987The Electoral College is enshrined in the Constitution itself, so getting rid of it would require the concurrence of two-thirds of both houses of Congress plus three-quarters of the state legislatures.

— Hendrik Hertzberg, The New Yorker, 6 Mar. 2006

In law, the word is used as a synonym of consent, as in "The Secretary of the Treasury obtained the written concurrence of the attorney general." Here's a presidential example:

If the President declares in writing that he is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, such powers and duties shall be discharged by the Vice-President as Acting President. … If the President does not so declare, and the Vice-President with the written concurrence of a majority of the heads of the executive departments or such other body as Congress may by law provide, transmits to the Congress his written declaration that the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office, the Vice-President shall immediately assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.

— Application of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to Vacancies in the Office of the Vice President, November 1973

Consent

The parent of consent is Latin consentire, a mutual joining of the prefix com- (meaning "with," "together") with sentire ("to feel"). The notion of "feeling together" is implied in English's consent, which denotes agreement with, compliance in, or approval of what is done or proposed by another. Consent is used as a noun or a verb with the meaning "to agree" or "to give permission."

He shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.

— U.S. ConstitutionHe consented to the search of his Mercedes, and officers recovered about 54 ATM receipts, four credit cards and six gift cards.

— Trish Mehaffey, The Gazette (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), 6 Nov. 2019

And, of course, children need parental consent to go on school trips.

In law, consent is specifically used for the voluntary agreement or acquiescence by a person of age who is not under duress or coercion and usually who has knowledge or understanding. By "of age" is meant "age of consent," which is the age at which a person is deemed competent by law to give consent. Eighteen years old is the standard age of consent in the United States.

There is also "informed consent," which is defined as "consent to surgery by a patient or to participation in a medical experiment by a subject after achieving an understanding of what is involved."

Contract

English secured Anglo-French contract as a word for a binding agreement between two or more persons in the 14th century. Its roots extend back to Latin contrahere, meaning "to draw together" as well as "to enter into a relationship or agreement." Early popular contracts were of the matrimonial kind.

I am sure you are not angrie, seeing things past cannot be / recald; and being witnesses to their contract, will be also welwillers / to the match.

— John Lyly, Mother Bombie, 1598

But contract can refer to any agreement between two or more parties that is legally enforceable. Typically, a contract creates in each party a duty to do something (e.g., provide goods or a service at a set price and according to a specified schedule). It may also create the duty not to do something (e.g., divulge sensitive company information).

In the early 20th century, contract was snatched by members of the criminal underworld as a term for an order or arrangement for a hired assassin to kill a particular person.

But I should report, sir, that Scaramanga does not have a contract on me. He couldn't have missed me tonight. Instead he hit a chap at a club.

— Roger Moore (as James Bond), in The Man with the Golden Gun, 1974

Convention

Convention is a familiar word for a large meeting of people, usually lasting several days, to talk about their shared work or interests—a teacher or publisher convention, for example—or for some common purpose. In politics, a traditional convention is a meeting of the delegates of a political party for the purpose of formulating a platform and selecting candidates for office (e.g., the Democratic/Republican National Convention). Other conventions are fan-based, and there are countless such conventions centered on gaming, comic books, and the anime, sci-fi, and horror genres—to name a few. This use of convention is in keeping with its ancestry. The word is from Latin convenire, meaning "to assemble, come together." The Latin root also means "to be suitable" or "to agree," which is recognizable in the word's senses relating to established usage, customs, rules, techniques, or practices that are widely accepted and followed.

Words express whatever meaning convention has attached to them, and so it may be argued that the State has covenanted against this tax in express terms.

— Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Trimble v Seattle, 1914The author uses the convention of the first-person narrator who observes all but is not implicated in the action.

Another familiar use of convention is in law and politics where it is applied as a term for an agreement between two or more groups (as countries or political organizations) for regulation of matters affecting all—for example, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. There are also the Geneva Conventions, a series of four international agreements (1864, 1906, 1929, 1949) signed in Geneva, Switzerland, that established the humanitarian principles by which the signatory nations are to treat an enemy's military and civilian nationals in wartime.

Covenant

The word covenant is commonly associated with the Christian and Judaic religions. In the Old Testament, it designates agreements or treaties made among peoples or nations but more notably the promises that God extended to humankind (e.g., the promise to Noah to never again destroy the Earth by flood or the promise to Abraham that his descendants would multiply and inherit the land of Israel). God's revelation of the Law to Moses on Mount Sinai created a pact between God and Israel known as the Sinai Covenant. The Law was inscribed on two tablets and in biblical times were housed in a gold-plated wooden chest known as the Ark of the Covenant.

In secular law, covenant is used to refer to an official agreement or compact ("an international covenant on human rights"). It can also apply to a contract or a promise within a contract for the performance or nonperformance of some action ("a covenant not to sue").

The word also has verbal meaning: "to pledge or come to formal agreement." See Holmes' quote at convention (above) for an example.

EDITOR'S NOTE: There are other words designating various types of agreements—such as deal, pact, pledge, settlement, and treaty—but we promised only the A's, B's, and C's. We fulfilled that promise.